Freud's Athena, the Olive Tree, and the Permanence of Home

Note: I do not endose psychoanalysis.

Introduction

Among the antiquities he owned, Freud’s Athena, dating to the 2nd century AD, was of particular significance to him. The Greek goddess symbolised many concepts explored in his work—scholars have frequently localized psychoanalytic developments in the context of her image, from antiquity and Fin-de-siècle Vienna. Most relevant to Freud’s personal life however, may be her status as his protector. She was one of the two antiquities (along with the Jade Screen) that he first gave to Marie Bonaparte to smuggle to his new home in London.[1] But a salient question arises here: how could this weathered 4 1/8 inch statuette be a symbol of strength, when her staple weapon—her spear—was missing?

Scholars have advanced various answers to explain the idiosyncrasy, including its reflection of the Oedipal Complex and the losses of history.[2] In the theme of safeguarding and patronage, I will argue in this essay that her missing spear does not detract from her protective power, but rather accentuates its defining qualities for Freud. This conclusion follows from two considerations that stem from the statue’s representational similarity to the sacred olive tree of Athens: the centrality of Athena’s olive tree in the Athenian cultural imagination, and how Freud correspondingly used Athena’s statue as his own enduring marker for home and hearth.

The Sacred Olive Tree

By the west porch of the Erechtheion on the Athenian Acropolis, one can find an unassuming olive tree. While it has been uprooted and replanted throughout history, legend has it that this tree can be traced back to the one planted by the goddess Athena herself in order to win the right to be the city’s patron deity.[3] A crucial preliminary point emerges: while skilled at war, Athena does not destroy with her spear to gain the respect of the Athenians. Instead, it is her capacity for craftsmanship, wisdom, and justice. It is what she generates, the fruits of her tree, that make her a protector—not her capacity for violence. The olive tree would come to hold a distinct symbolic meaning that intermixed the foundational values of its home polis. I will focus on two aspects of this symbolism here, setting the tone for subsequent discussions about its reflection in Freud’s life.

Firstly, the tree became the foundation of the city, both materially and ideologically. Materially, it was incredibly versatile, as a building material, a staple crop, and a valuable export[4]—making it rather worthy of its designation by classicist Colin Renfrew as a catalyst for the development of Greek civilization itself.[5] Its multifaceted uses also extended into the conceptual realm. Certain olive trees growing in Athens known as moriai would be protected under ownership of the state due to their religious significance.[6] Olive branches would be minted on Athenian tetradrachm coins along with the image of Athena, her owl, and a crescent moon[7]—forming the four chief symbols that Athens self-identified with and chose to circulate throughout the Mediterranean. In disseminating images of the tree in religious and civic life, the Athenians were blending Athena’s virtues with their own, creating a novel ideological groundwork on which Athenian spiritual and secular self-representation was built. This representation would harmonize with the broader role of the olive branch as a token of peace, given as a wreath (kotinos; Greek: κότινος) to victors of the Olympic Games during a time when Greek city-states were under an oath of truce—imparting upon the tree an additional diplomatic, rather than warlike, meaning.

Secondly, despite its physical delicacy, the olive tree of Athens demonstrates a remarkable ideological resilience. A lone tree cannot be impervious to time or destruction—the lonely tree on the Acropolis frequently suffered fires and disfigurements by invading armies. As Herodotus writes in Histories (c. 5th BCE),[8] it was burnt down during the Persian invasion of the city. However, when the Athenians decisively defeated their enemies at the Battle of Plataea (497 BCE) and returned to their city, the tree would resprout from its roots (VIII. 40). Herodotus’ story tells us that while the sacred tree is only corporeal, it is unable to be fully destroyed—it is saved in a similar manner multiple times throughout its long history, a small branch always being recovered from its ancestor to be replanted again in the same location. We must be careful in taking this tale too literally, as it is counterfactual to assume the tree standing today is biologically-related to the one which stood in its place more than two millennia ago. Rather, the tree survives in Athens not because it is physically hardy, but because it transcends its physical boundaries by becoming an idea—and whilst organic matter can decay, ideas cannot. The sacred tree, more than just a figurative ideogram, was the symbolic core of the city and its people.

Thus, the first connection we introduce to Freud’s Athena is a material one. Freud’s Athena lost its spear in-part because of how easily bronze is weathered. However, we know that the weapon is not important for her status as the city’s protector. It is her tree and its capacity for peace, renewal, and endurance, that gives her authority in Athens. Whilst the frailty of the metal does mean that the statue displays its materiality more so than a more changeless material, this only makes it a more organic parallel for the olive tree, a paradoxically delicate, yet durable, marker for home. It is to these ideas that we will return when we examine the tree’s incarnation in Freud’s life.

The Spearless Statue

What I will argue in this section is simply that the small Athena statue was Freud’s own olive tree. It was rich with symbolic meaning that he interacts with through his work, including the derivation and reflection of the origins of psychoanalysis and its subsequent ideas. However, it served an equally-important and perhaps overlooked role as his embodiment of home. “Home” here does not only hold a literal meaning (i.e. family, household), but also a figurative one. Like the Athenians and their sacred tree, the statue was the place where Freud latched the concepts he identified with—the material home of his ideas.

Freud’s Athena occupied a central place on his desk, where it both supervised and inspired his work. It was positioned among his collection of archaeological figures of mixed ancient origins and divine providence, where it was a cornerstone for his diverse psychoanalytic writings. The most famous concept attributed to the Athena and her lost spear is the idea of female castration and the Oedipus complex, but the statue is also associated with myriad other ideas relevant to Freud’s work: the recuperation of traumatic memories,[9] the psychoanalytic perspective on Greek myth and tragedy,[10] and the enabling of a psychoanalytic connection between analyst and analysand through the touch of the past.[11] In effect, similar to the olive tree’s place as the foundation for bi-dimensional Athenian representation, it held the same versatile role in Freud’s personal construction of psychoanalysis as something that held both spiritual and secular meanings. “Spiritual” did not mean that Freud literally believed in the existence of the gods as if they were embodied in their statues, but rather what they denoted — i.e. how the religious themes from mythology later informed a spiritual interpretation of the human psyche, and how this process illustrated certain immutable truths about human nature.

Perhaps the most important analogies in this right emerge in the narrative of Freud’s displacement by the Nazi occupation of Vienna. We know that the statue was one of the first he chose to smuggle out to his new home in London, given to his friend, Marie Bonaparte. He would later write to her after the move on June 8, 1938: “The one day in your house in Paris restored our good mood and sense of dignity; after being surrounded by love for twelve hours we left proud and rich under the protection of Athene.”[12] In his letter, he conveys that the statue was his guardian on the uncertain journey from Vienna, and it was able to accomplish this faultlessly without a weapon. But how?

The first piece of supporting evidence we have is from Burke’s article, who expresses that the antiquities were unpacked in a room that was beside the backyard of his new house in Maresfield Gardens. The natural world was always a place of “regeneration and inspiration”[13] for Freud since earlier in his life, and by placing his collection next to it with Athena at the centre, Freud would inseparably link the statue with the complementary ideas that the natural world provided to him. After the hazards of the Nazi invasion, his statue-garden amalgam became his peaceful marker of home, reincarnated when he first placed Athena in its new setting. It was like the Athenians coming home to see that a new sprig of their olive tree had regrown.

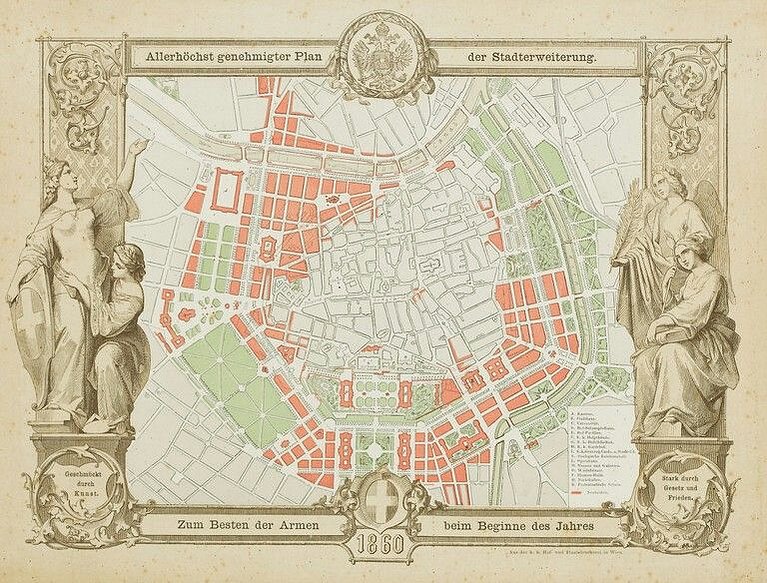

Aptly, the statue did not move alone but brought along with it vestiges of its past—Vienna, the birthplace of psychoanalysis, continued to “live-on” in the statue. Whilst Freud could not return to Vienna physically, it was like the city sprung forth again when he established the statue in his new home. Accordingly, the statue, and its counterpart on the Ringstrasse, continued to bring unity to the diverse and idiosyncratic picture of psychoanalysis throughout Freud’s later life. This notion has important implications for the endurance of Freud’s ideas.

Psychoanalysis started as “idiosyncratic theory of the mind,”[14] but strove to be something more within the grander scientific and humanistic trends of its period. This ambition is said by Schorske to be seated in the image of Athena.[15] As the Ringstrasse’s Athena served to unify Vienna’s eclectic architecture, it simultaneously pulled together in a loose union the ideas of psychoanalysis under the same iconographic representation. As Zaretsky would write, the complexities of psychoanalysis are best understood as the "form of consciousness that a new historical epoch, characterized by new productive forces and new life forms, had of itself.”[16] It was a concept saturated with meaning, connecting the underlying psychic, mythical, and scientific trends of the period. Most consequentially, Zaretsky argues that it symbolizes the life-force of the Vienna in which Freud lived—much like how Athens co-opted the living tree as their own vehicle for self-representation and dissemination of their identity, the spread of psychoanalytic ideas also took along with it traces of the Fin-de-Siècle Vienna where it was born.

While certain psychoanalytic interpretations of the mind dissolved to make way for new scientific developments in the 1960s, Zaretsky asserts that psychoanalysis continues to survive in mainstream society within the way that we examine conflicting social, political, or cultural truths. These conflicts arise at every point in history, and the best path to progress has always been understanding the human motivations behind them: “in other words...understanding our own nature including what is in our day most interesting about it.”[17] Thus, the psychoanalytic mode of thought retains its preeminence in the interpretation of subliminal instincts, of ourselves and our relationships with others. The branches of psychoanalysis, rooted in Vienna and the city’s later reflection in Freud’s Athena, have been saved and replanted up until the modern day. Like the original olive tree on the Acropolis, psychoanalysis transcends its temporal and spatial dimensions to become something greater. It is able to be transformed and reconstituted, but never erased. It is the progenitor of a certain cultural consciousness, a way of thinking about human nature that originates from the home which it symbolizes—one that ultimately achieves, through rebirth, a timeless quality.

Conclusion

To conclude, this essay has explored two corresponding themes: the station of Athena’s sacred olive tree in its home city of Athens, and how Freud’s statue of Athena became his own version of the olive tree, embodying the endurance of his diverse psychoanalytic ideas and their origins in Vienna.

In returning to the question of why the missing spear is insignificant to Freud when assessing the Athena’s power, it ultimately becomes a reflection on whether it was her spear or the olive tree that she planted that made her a protector. For Freud, as for the Athenians, it was the latter—the Athena was never just a statue for Freud, nor was the olive tree just a plant for the Athenians. Rather, they were both symbols that surpassed their terrestrial boundaries to become perpetual, serving to establish the permanence of home.

1 Janine Burke, The Sphinx on the Table: Sigmund Freud’s Art Collection and the Development of Psychoanalysis, 1st U.S. ed (New York: Walker & Co. : Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers, 2006): 328.2 Jana Funke, “The Queer Materiality of History: H.D., Freud and the Bronze Athena,” in Sculpture, Sexuality and History: Encounters in Literature, Culture and the Arts from the Eighteenth Century to the Present, ed. Jen Grove (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019), 221–44, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95840-8_10.

3 Patricia A. Marx and Jean-Robert Gisler, “Athens NM Acropolis 923 And The Contest Between Athena And Poseidon For The Land Of Attica,” Antike Kunst 54 (2011): 21–40.4 Hudson T. Hartmann and Plato G. Bougas, “Olive Production in Greece,” Economic Botany 24, no. 4 (1970): 443.

5 Colin Renfrew, The Emergence of Civilisation: The Cyclades and the Aegean in the Third Millennium BC (Oxford : Oakville, CT: Oxbow Books ; David Brown Book Co, 2011).6 Sophocles. and R. C. Jebb, Sophocles; the Text of the Seven Plays, xiv (Cambridge [Eng.]: University press, 1914): 289, //catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001845950.

7 John H. Kroll, “The Reminting of Athenian Silver Coinage, 353 B.C.,” Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 80, no. 2 (2011): 229, https://doi.org/10.2972/hesperia.80.2.0229.

8 Herodotus and A. D. Godley, The Persian Wars, vol. IV, The Loeb Classical Library 117–120 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1981).

9 Tim Martin, “From Cabinet To Couch: Freud’s Clinical Use Of Sculpture,” British Journal of Psychotherapy 24, no. 2 (May 2008): 184–96, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0118.2008.00076.x.10 Jennifer Eastman, “Freud, the Oedipus Complex, and Greece or the Silence of Athena,” The Psychoanalytic Review 92, no. 3 (June 2005): 335–54, https://doi.org/10.1521/prev.92.3.335.66536. 11 Funke, “The Queer Materiality of History: H.D., Freud and the Bronze Athena”: 221–44

12 Ernest Jones 1879-1958., The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud, 1st ed. (New York : Basic Books, 1953): 226.13 Burke, The Sphinx on the Table: 339.

14 Eli Zaretsky, “Why The Freudian Century: Reflections on the Statue of Athena,” American Imago 68, no. 4 (2011): 680.15 Carl E. Schorske, Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture, 1st Vintage Book ed (New York: Vintage Books, 1981): 44.

16 Zaretsky, “Why The Freudian Century: Reflections on the Statue of Athena”: 681.

17 Zaretsky, “Why The Freudian Century: Reflections on the Statue of Athena”: 687.

Bibliography

Burke, Janine. The Sphinx on the Table: Sigmund Freud’s Art Collection and the

Development of Psychoanalysis. 1st U.S. ed. New York: Walker & Co. : Distributed to

the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers, 2006.

Eastman, Jennifer. “Freud, the Oedipus Complex, and Greece or the Silence of Athena.” The

Psychoanalytic Review 92, no. 3 (June 2005): 335–54.

https://doi.org/10.1521/prev.92.3.335.66536.

Funke, Jana. “The Queer Materiality of History: H.D., Freud and the Bronze Athena.” In

Sculpture, Sexuality and History: Encounters in Literature, Culture and the Arts from the Eighteenth Century to the Present, edited by Jen Grove, 221–44. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95840-8_10.

Hartmann, Hudson T. and Plato G. Bougas. “Olive Production in Greece.” Economic Botany 24, no. 4 (1970): 443–59.

Herodotus, and A. D. Godley. The Persian Wars. Vol. IV. The Loeb Classical Library 117–120. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1981.

John H. Kroll. “The Reminting of Athenian Silver Coinage, 353 B.C.” Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 80, no. 2 (2011): 229. https://doi.org/10.2972/hesperia.80.2.0229.

Jones, Ernest, 1879-1958. The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud. 1st ed. New York : Basic Books, 1953.

Martin, Tim. “From Cabinet To Couch: Freud’s Clinical Use Of Sculpture.” British Journal of Psychotherapy 24, no. 2 (May 2008): 184–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0118.2008.00076.x.

Marx, Patricia A., and Jean-Robert Gisler. “Athens NM Acropolis 923 And The Contest Between Athena And Poseidon For The Land Of Attica.” Antike Kunst 54 (2011): 21–40.

Renfrew, Colin. The Emergence of Civilisation: The Cyclades and the Aegean in the Third Millennium BC. Oxford : Oakville, CT: Oxbow Books ; David Brown Book Co, 2011.

Schorske, Carl E. Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture. 1st Vintage Book ed. New York: Vintage Books, 1981.

Sophocles., and R. C. Jebb. Sophocles; The Text of the Seven Plays. xiv. Cambridge [Eng.]: University press, 1914. //catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001845950.

Zaretsky, Eli. “Why The Freudian Century: Reflections on the Statue of Athena.” American Imago 68, no. 4 (2011): 679–88.